Don't Let Black History Month End Without Leaning into Black Stories

About half, maybe more, of my teachers from kindergarten through twelfth grade were black women.

Ms. Smith.

Ms. Craig.

Ms. Collins.

Ms. Taylor.

Ms. Weaver.

Ms. Ermel.

Ms. Kindle.

That means I can remember coloring pictures about Jesse Jackson’s campaign for President when I was in first grade. It means in second or third grade I watched Roots with the rest of my classmates. It means from a young age I heard a robust history of the slave trade, the underground railroad, the harsh realities of emancipation and Jim Crow, the Civil Rights movement and heroes like Dr. Martin Luther King, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Ruby Bridges. It means I always had a steady diet of literary giants like Phylis Wheatley, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Maya Angelou, August Wilson, and James Baldwin. It means we debated affirmative action and school integration in my high school social studies classes. It means my parents drove me all over the city to my friends’ homes in Montebello, Park Hill, Swansea, and Sun Valley on Saturdays. It means some of my longest held and dearest friends are black women.

Thank you, Mom and Dad, for your commitment to this kind of education for me. Thank you for making it a priority for me to learn from teachers of all cultures and to grow up with kids of all colors. I count this as one of the most valuable gifts I’ve ever been given.

An upbringing overflowing with varied cultures and colors wasn’t my parents’ idea though. And it didn’t originate with progressive ideologues. It was the very good idea of our God in heaven, the Maker of all men, the Creator of all shades of melanin, all hair textures, and every hue of every iris.

We see God’s priority for a multi-ethnic family in his promise to Abraham. In Genesis 12 he tells Abraham that all families will be blessed through him, and in Genesis 17 that Abraham will be the father of many nations.

Jesus renews this vision in the Great Commission in Matthew 28, telling his followers to go to all nations to teach them and baptize them into his family.

We see the ethnic diversity in the body of Christ on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2) when men and women “from Parthians and Medes and Elamites and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, Cretans and Arabians” hear the mighty works of God in their own language ( Acts 2:5-11).

Paul reminds the Colossians that even Greeks and Jews, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarians, Scythian, slaves, and free men are all united in Jesus Christ (Colossians 3:11).

And of course there’s that great family reunion that we long for in the New Heavens and the New Earth when “a great multitude that no one could number, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, clothed in white robes, with palm branches in their hands, and crying out with a loud voice, ‘Salvation belongs to our God who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb!’” (Revelation 7:9-10).

Christianity is multi-ethnic from the first to the last, from beginning to end, and forever and ever. Christians, then, know better than any other people on the planet how essential it is for us to learn from, listen to, and love voices that come from bodies that don’t look like ours. We were created for unity amidst our diversity, to share various perspectives with one another, to sharpen each other. Ethnicities were our God’s idea and he died for every one. Jesus will not return until every people group has heard the true story of his great love (Matthew 24:14).

We are better together.

God’s intentional design of diversity, then, makes Black History Month a uniquely sweet time for American Christians to listen to black voices. Our nation has a specific and evil history when it comes to the trafficking of Africans and the treatment of black Americans. And the American church has a specific and lamentable history of segregation and complicity that must be acknowledged and repented of.

Black history isn’t like any other history in our nation. And one month isn’t enough. But it’s a start in carving out time, attention, and affection in the hearts of Christian Americans to better know the history and the present experience of our black siblings. To my white brothers and sisters in Christ—especially those who live in a predominantly white community, as I do now—we must strive to find and listen well to black voices. Fight complacency.

“As we have opportunity, let us do good to all people, especially to those who belong to the family of believers” (Galatians 6:9, 10). May we listen hard to our black bothers and sisters in Christ, may we weep with them, rejoice with them, march with them, eat with them, live near them, work with them, send our kids to school with them, see Christ in them.

I love these moving words of author Dante Stewart:

The story I want to tell is this: Black people are human and worthy of love. We are not heroes. We are not villains. We are human, as beautiful as we are terrible. Our lives are not just resistance. Our lives are not just lessons.

Our stories — and our futures — are the ways we have stood up for what’s right and kept on living when dreams were deferred, hopes unrealized, lives lost, and bodies wearied, and our hearts beating fast as our feet moved across red carpets in old churches rejoicing that we are given of life. These stories are our shining joy. They have become gospel to a people bent and broken.

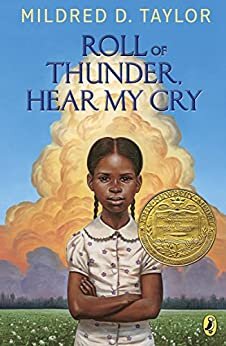

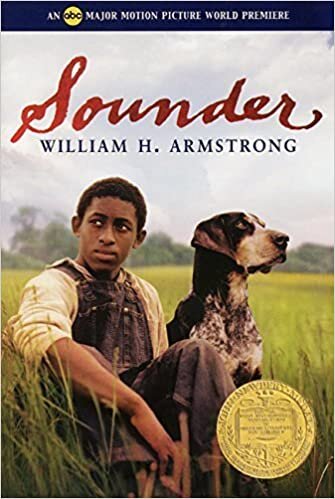

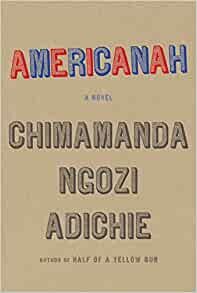

Here are some books, movies, and podcasts that help to tell the stories of black Americans both present and past. They have taught me well over the past few years. Maybe you’ll see something below to dive into during our final weekend of Black History Month. And I hope you and I will both keep diving. The list is by no means exhaustive, and I’d love to hear your ideas too. Please share them in the comments.

For further listening and reading from Jen Oshman:

All Things Episode 3: Why Bother with Black History?

Recommitting to the Imago Dei on Dr. King’s Birthday

The Gospel Demands that we be Bridge Crossers

Pursuing Racial Reconciliation in our Living Room

Pursuing Racial Reconciliation in our Living Room—Take Two

Empathy, Hidden Figures, and Philando Castile

Unearthing the Roots of Our Collective Racial History and Identity

Movie Ideas for the Whole Family on this MLK Day

All Things Episode 20: "Go back to where you came from:" a Christian Response