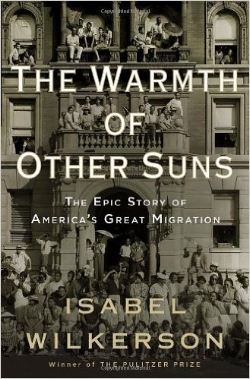

Without Question, The Best Book I Read All Year: The Warmth of Other Suns

The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration has given me pause every day since I read it this summer. The history I learned reverberates through my thinking about my black friends’ families, histories, and experiences, as well as the status of my own family. It was worth the very long read, as it speaks to our nation’s current race crises. I wish everyone would read it, but especially my white friends.

Author Isabel Wilkerson spent 15 years researching to write this historical epic, which follows three African Americans through the Great Migration. Many Americans (like I was prior to reading the book) are unaware of the Great Migration, the greatest untold story of the 20th Century. Lasting from 1915 to 1970, it is the movement of 6 million black Americans from America’s south to America’s west and north to escape the Jim Crow caste system and harsh treatment and to improve their lives and futures. The migration required great courage and had unforeseen consequences.

The book is an account of the true stories of three brave but typical migrants. Three black southerners who made the decision of their lives and followed three main streams of the migration: Ida Mae Brandon Gladney was a sharecropper’s wife who left Mississippi for Chicago; George Swanson Starling was a college student and citrus picker from Florida who headed to New York; and Robert Joseph Pershing Foster was a surgeon who served in the United States Army and then drove across the desert from Louisiana to California.

Wilkerson invested hundreds of hours interviewing these three, as well as their family and community members. Using their own words, she provides firsthand accounts of what it meant to be born black in the deep south in the early 1900s: the abuse of women, the segregation, the lack of educational and employment opportunities, the impossibility of advancing oneself, the lynchings, the violence. But also what it meant to be black and migrate north: the decision alone was often life-threatening, the circumstances found in the north were not easy and rarely fair, equal, or without fear of violent reaction from the migrant’s new community.

While I knew the American historical context of Gladney, Swanson, and Foster’s era, hearing their personal stories often made me wince and weep. I had to pause the audio book more than once just to take a deep breath and utter a prayer either of thanks to the Lord for their strength and perseverance or for comfort for them even now in what they have lost. Their lives bear a heavy witness that I cannot fathom. They and 6 million other brave pioneers dared to pursue better for themselves and their families, forever and positively changing the sociological makeup of our nation.

Inevitably, I pondered my own family’s history as I read. My mother’s father was born the thirteenth child to white cotton picking parents in Texas and moved north to Illinois in 1938. Ida Mae Brandon Gladney was also a cotton picker and also migrated north to Illinois. My grandmother’s father was a conductor on the Illinois Central, the train line that brought many millions north in the Great Migration and also the train line on which George Swanson Starling was a porter. My own mom unknowingly witnessed the Great Migration as a young girl riding the rails back and forth with her grandfather.

It’s impossible to read The Warmth of Other Suns and not wonder about your ancestors who were contemporaries of the characters and then to ponder how and why their experiences were vastly different. My mother’s family migrated north from Texas and my father’s from Texas, Florida, and Georgia. They moved for better jobs, homes, and education and were granted all with ease and without fear because of their white skin. This book rightly reminds me of the lineage of privilege from which I come, which I did not earn, nor do I deserve.

If white Americans will read it, The Warmth of Other Suns has everything to contribute to the conversations that only happen in all-white contexts: What are they so mad about? There is no more racism, why can’t they get over it? Things are more than equal—in fact, I didn’t get the job because I’m NOT black. I shouldn’t be made to feel guilty because I’m white. My ancestors worked hard too.

The Great Migration ended just one generation ago. Horrific atrocities victimizing black Americans in the south (and more subtle atrocities in the north) were the norm not that long ago. There is still much to be acknowledged, much to be repented of, and much to be forgiven. The Warmth of Other Suns reveals the fractures that remain in our collective history. For those who will pick it up and take it to heart, it will provide a sober placement of oneself in our nation’s history—a concrete narrative of where we’ve been, why we are where we are right now, and how we might, with a humble acknowledgement of one another, move forward.